Currently I am working on three projects.

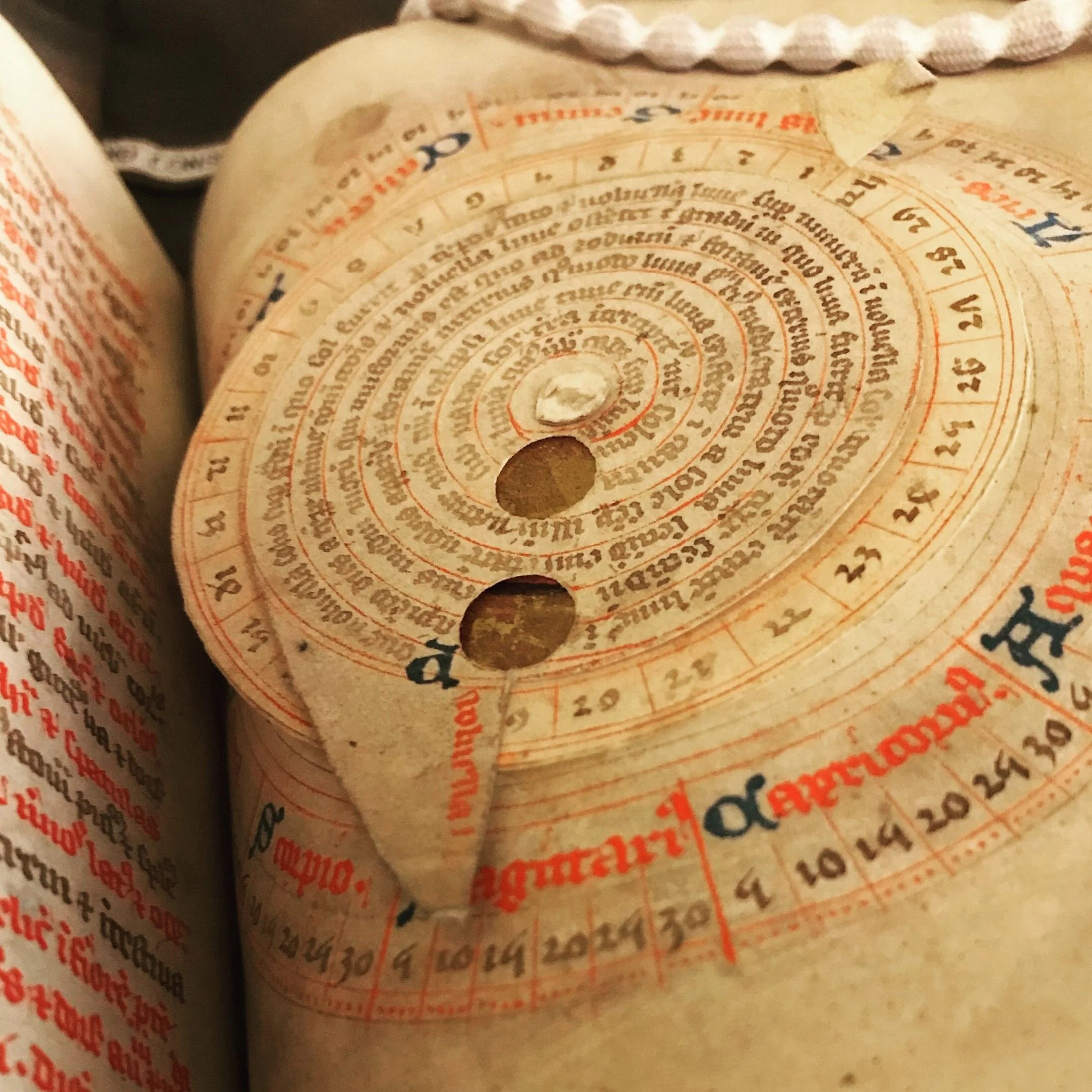

The first is transforming my dissertation into a book. At the broadest level, my dissertation asks: how did ideas about observation in late medieval medicine impact the pictorial representation of the human body? Observation — both as a component of a nascent theory of scientific communication and as a practical step in examining a patient — appears in many guises in medical texts produced in late medieval England. I argue that images in medical manuscripts don’t merely reflect this emphasis on observation. Rather, surgical figures and diagnostic diagrams employ strategies and techniques that allow the images themselves to serve as tools for honing one’s visual judgment.

While quarantined far from campus, I began work on a second project that analyzes a local architectural landmark. A federal prison in Lewisburg PA was built in the 1930s in the style of a fourteenth-century Italian palazzo. Inside, gothic arches, timber vaulted ceilings, and brass room dividers that resemble late medieval choir screens bring a distinctly medieval sensibility to the first prison designed in the US with a distinctly reformist and rehabilitative mission. I am using USP Lewisburg as a case study to analyze how an imagined medieval past and a bucolic architectural symbol matched shifting public attitudes toward imprisonment.

I am also in the early stages of a major research project that examines a group of alabaster devotional panels mass-produced in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century England. These small, sculpted images of saints and biblical scenes are thought to have been produced in workshops in England’s East Midlands for a growing middle class of consumers. I compare the development and infrastructure of alabaster production and the well-documented advent of urban manuscript workshops in Britain to investigate the role of the workshop in facilitating the rapid spread of image-based knowledge. This project directly compares the milieu of alabaster production to modes of serial image-making that bridge the perceived divide between medieval and early modern.